I love art. But I can barely etch a stick figure. I have to translate what I see into words. Sometimes the tension between my deep appreciation for visual art and my inability to produce it feels like a strange illness. So I compensate in other ways. I write about art. I gorge myself on gallery shows, museum exhibits, web sites and magazines about art, coffee table books, art-related films, and graphic novels. Recently, I’ve been seeking out documentaries about the creative lives of artists, finding inspiration in their processes.

My latest discovery is the New People Artist Series, produced by Viz Pictures. The first video came out in 2007, and there are now six in the series. Each DVD profiles a Japanese artist, providing a close-up view of his or her inspirations and creative process. And by close up, I mean close. Much of the footage comes directly from the art studio, where we peer over the artist’s shoulder, watching them paint or draw or sculpt in preparation for a major exhibition. Now I’m someone who can actually watch paint dry, and find that fascinating, so I’m probably an ideal audience member for this series, in which sometimes viewers are, literally, watching paint dry. Or we are watching an artist microwave a meal, or smoke a cigarette, while he waits for the paint to dry.

I love the focus on process and inspiration in this series. We learn little about these artist’ childhoods or personal lives, and there is not a lot of glamour. We don’t gawk at the public persona of the artist. Instead we glimpse the sacrifices they’ve made for their art, living in modest quarters and nondescript neighborhoods. The focus is on the art and how it’s made. In the three DVDs I have viewed so far, we are invited to observe relatively quiet artists who are developing their works brush by brush, line by line. They are filled with inspiration for anyone who works in a creative field.

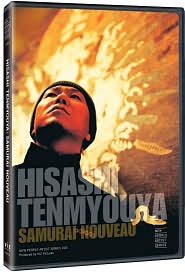

In Hitashi Tenmyouya: Samurai Nouvau, we watch the artist painstakingly apply layers of gold foil, reviving some traditional techniques in Japanese art, which he then mixes with more modern techniques. We watch him make tiny pencil marks on transparent paper to create scrolls with elaborate details. He is a model of patience and perseverance, crouched over his canvases, blowing away graphite dust. Somehow, all these scratch marks combine to make jaw-droppingly detailed scrolls, drawings and paintings that are exhibited and receive international acclaim. His process reminds me that even on writing days that feel unproductive, all those words, my own little scratch marks, really can add up to something in the end.

In Yayoi Kusama: I Love Me, the avant-garde, pink-haired artist, who is known for her fascination with polka dots, races the clock to create 50 massive drawings with black markers. The camera lingers on her as she outlines, then colors in, dot after dot after dot, between strangely beautiful squiggle and lines and wide staring eyes. There is an element of suspense here, considering the artist’s advanced age, her growing fatigue, her own sense of mortality. Will she complete the series in time for the exhibition? And there are lessons for writers and artists in other media to take away, too. Her bursts of energy and her loyal assistants carry her along on her project, reminding us of the power of artistic vision — and the power of having a supportive team on your side, to help your work see the light of day. Kusama is also a poet. One of my favorite moments in the film is when she reads through a poem she published years ago. She blinks in astonishment when she is done and exclaims, “This is very good!” It’s so easy for us to criticize our own work, especially once it’s been published or produced, yet Kusama unabashedly delights in her finished products.

Traveling with Yoshimtomo Nara also has a quiet element of suspense as we follow an introverted artist around the world, watching him set up exhibits in various cities and ultimately stage a massive multimedia installation piece in collaboration with others. The suspense arises in the tension between the artist’s self-processed introverted tendencies and his desire to connect with his audience (particularly with children, who are captivated by his whimsical drawings and seem to revere him like a rock star). He also searches for ways to come out of his shell and connect with other artists. In the end, we see how his encounters with others greatly impact his work. This documentary teaches artists in any medium about the power of collaboration, and about how we find satisfaction in reaching an audience — sometimes in surprising ways.